The Buddhist Concept of Freedom

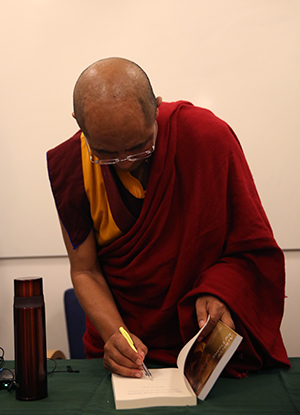

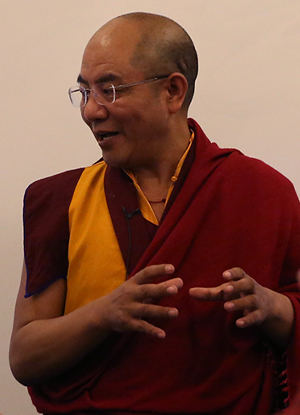

While visiting Kumla Prison in Sweden, 2017, Khenpo Sodargye discusses with the inmates the kind of freedom that truly matters, which enables us to be free at all times, even if we are physically imprisoned. He shows us that even though we may all appear to be different, we can break through cycles of thoughts and emotions that lead us to suffer, and by taking advantage of every opportunity, we can develop a disciplined practice, that will reward us throughout our life.

“When we have the sense of self-protection or self-discipline, we may seem to be restricted in our behavior, but there’s a bigger picture that is very important to consider and that can transform our lives.”

Realizing the Nature of Mind Is the Ultimate Freedom

Happiness Lies in the Mind

I’m very happy to have the opportunity to talk with you today. After my talk, which will last about one hour with translation, we can have a Q&A session in order to clear up any questions you may have. In order to make this talk happen, I have traveled more than 200 km from Stockholm, and when I go back later, I will have traveled more than 500 km, which I’m really happy to do.

I’ve visited some 20 prisons in all kinds of places. I’ve also read about imprisonment from books. In the 20thcentury, life in the majority of prisons was pretty harsh, as can be seen from photographs taken on the inside. Later, prison management was gradually globalized, and the prisons I’ve been to are all of this modernized kind. As I was being shown around, I saw that this one is one of the best among all prisons I have seen, considering its facilities, such as the places for study and for housing. There are some prisons in Africa that I would have liked to visit on this tour but it hasn’t worked out because of my tight schedule. I plan to visit them next year. I’ve heard that the conditions in these prisons are pretty grim. Maybe this has something to do with the level of economic development and poor social security in African nations, as I learned from my eariler visit there.

Today I’ve been invited to talk about the Buddhist concept of freedom. Some of you may be religious people and some of you not. Personally, I believe whether we are religious or not, human beings all intrinsically possess kindness. This is a shared idea within all religions. I have held several symposiums on topics such as peace and happiness, with members from various religions including Christianity, Catholicism, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, creating the chance for different religions to learn from one another, and to seek happiness from within, because happiness is important to everyone irrespective of faith.

Regardless of whether we are Easterners or Westerners, people of all nations share one thing in common: we all seek happiness and wish to avoid suffering. We think we are different because people of different nations and places differ in their habits, traditions, and conventions. Take drinking coffee as an example. People in the Tibetan region think too much coffee is not good, but drinking coffee several times a day is very common here. I just came from New York. To many Americans, one cup of coffee isn’t enough to deal with the afternoon tiredness. However, many Chinese agree that it’s ok to drink no more than one cup of coffee a week, otherwise, it will be bad for one’s health. As I see it, it’s due to the difference of cultures and ideas between the East and the West. At home, drinking one cup of coffee makes me worry about my health, but here, drinking three cups in one day is enjoyable for me. But say you were in the Tibetan region, maybe after a couple of days you wouldn’t want to drink coffee anymore. It’s good to see coffee in your rooms by the way.

Despite all the various differences between cultures, and because all of our sorrows and joys arise from our mind, the important practice of observing the mind is a constant. ‘Observing the mind’ means you stay mindful of the present moment, of what you are thinking or what you are doing right now. As I’ve learnt about the teachings of different religions, actually observing our own mind is found in all of them.

How Do People Understand Freedom?

Everybody believes freedom is important. However, the understanding of what defines freedom, can vary tremendously. Some people enjoy physical freedom—going where they want—but their minds are not free; some who are free mentally find themselves physically challenged; some are deprived of freedom both physical and mental; while others enjoy unlimited freedom. So how then can one be free mentally but not physically? For example, if one is incarcerated. Some people, although physically free, are plagued by their excessive desires, destroying the freedom of their minds. Some are dominated by their intense anger or hatred, which makes them unhappy and not mentally imprisoned. Some are haunted by their raging jealousy, and are not happy or free, not even for a second. Due to our different value systems, for some people, it is meaningless to live in the world without freedom. As John Patrick Henry, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, famously said, ”Give me liberty or give me death.” To him, death was preferable to living a life without freedom.

Freedom in this context, however, mainly refers to one’s ability to act according to one’s own desires. For example, the ability to go anywhere one pleases, say whatever one feels inclined to, and to think about whatever comes to mind. This American idea of freedom has had a huge impact on today’s youth. Even though the US is a relatively young country, only some 200 years old, its culture has circulated around the world. Although Europe, similar to the Tibetan region, is blessed with very old cultures and traditions, whether religion, architecture, art or literature, its younger generations today are taking many of their cues from Hollywood movies and music videos. But freedom is much more than this American “do whatever I please” version. ‘What freedom really is’ is a question that never fails to occupy the minds of religious and non-religious scholars alike.

Realizing the Nature of Mind Is the Ultimate Freedom

There is a fundamental component of freedom I’d like to talk about now. As the marvelous thinker Hegel said, “autonomy is the most fundamental freedom which a person possesses.” Autonomy, or self-governance, is not actualized by way of force or discipline. Rather, it is best actualized through realizing the nature of our mind. Let me explain. When we have a sense of self-protection or self-discipline, we may seem to be restricted in our behavior, but there’s a bigger picture that is very important to consider here and that can transform our lives.

The idea of self-protection and self-discipline is common to most religions. In Buddhism, it’s called discipline. As one progresses on the Buddhist path, the number of precepts, or rules we follow, increases as well. In religions like Christianity and Islam, they also have their own precepts for governing people’s behavior. This might seem counterintuitive, but the purpose of these precepts is to enhance, not dampen, our spirit. The importance of precepts isn’t generally appreciated by young people today, but as they get older and gain more experience, they will come to see the value.

I don’t know your state of mind, but I’m sure it’s not so bad given the decent external circumstances here. The officers seem very kind. All of the ones I have met have been very gracious towards me. Maybe it’s because this is my first time here. Of course, I appreciate that there are many things that might be bothering you now. For example, you can’t be with your families, you are prohibited to travel and you can’t hang out with your friends or head out to parties as usual. This may be a completely new environment and a new way of living for you. I realize that’s tough. But if we try to look on the bright side, maybe being confined here won’t generate so much suffering.

In my own life, I was supposed to become a teacher, but decided before I’d even graduated school to be a monk instead, and did exactly that when I was 23. When I became a monk, I only had a few dozen Chinese Yuan in my pocket. There was no electricity, no tap water in the place where I lived as a young monastic. When winter came, I had no central heating. I had a small bag of tsampa (barley flour) for food to live on over a month. There was no rice, sometimes only a handful of noodles for food, and I had to find and chop wood in the mountains myself for firewood to cook meals and make tea with. There were no green vegetables whatsoever. When I was reading at night, the only light came from burning incense. But during that period, sometimes I was really happy because I got the chance to study Buddhist teachings every day. Sometimes I was also very sad because I couldn’t see my parents or my sibling. I barely contacted my family in the first five years of my monastic life. That was tough, but overall it was a good opportunity for me to study.

If you devote your time in prison to study, then something wonderful might happen—your intelligence would be significantly enhanced. It’s easy to cultivate our intelligence and competence when things go smoothly.

Transform Hard Times Into Opportunities

Transform Hard Times Into Opportunities

It will be a pleasant time to spend if you take your sentences as a chance to do retreat or practice, regardless of your faith. As I learned from some Catholic friends, the duration of their ascetic practice is quite long. During that time, practitioners only take one meal at noon every day. They barely sleep, and even if they do, they simply sleep on the floor. Such a way of ascetic practice is very helpful to enhance the mind because it provides the opportunity to reflect on what’s important. In Buddhism, there’s the practice of meditation or yoga. To do meditation requires one to cut off from all kinds of distractions and to calm the mind down. This environment you are in here is perfect for meditation.

I’m not saying this because I’m free physically. It’s from my heart. Although right now I have lots of things to deal with and while giving lectures all over the world, there is the possibility that I might commit a crime and end up in jail because of one wrong thought. Even though I actually have done nothing wrong, I might be falsely accused and found guilty because negative karma from a previous life has ripened in this life, which results in being imprisoned for a long time. Or, I might be sent to prison simply because of my religious belief, something which happened around the world in the last century. Who knows, doing time behind bars might be how I spend my later years. If that day came, I would use those circumstances as a good opportunity to practice. It would also be a good time to study because I love reading. Truth be told, without books, I might get very upset. I noticed there are lots of books in your dorms. If I had books with me while I was incarcerated, it wouldn’t be so bad.

There is a prison back where I live at which I gave lectures. When I was giving the first lecture, they had no books whatsoever, so I worked to build a library in each of the four wards of the prison. When I went to the prison the second and the third time, I was told inmates who loved reading had already finished several books. One prisoner who had been an officer before imprisonment told me during his four year sentence there, he had finished reading over 20 books, something he had never done before.

If you devote your time in prison to study, then something wonderful might happen—your intelligence could be significantly enhanced. It’s easy to cultivate our intelligence and competence when things go smoothly. However, even the low points of our lives can also work the same way if we can transform such adverse circumstances into good opportunities to improve ourselves through appropriate methods. There was a very renowned Buddhist practitioner back where I am from. Unfortunately, he was imprisoned for 19 years, which he used as an opportunity for him to study. When he was finally released, he said he’d spent 19 years at “college”. He’d gained so much knowledge in prison that he hadn’t gotten through his formal education.

Among all the causes and conditions that led us to being imprisoned here right now, the major cause is ourselves, because it is mainly due to our previous karma and our improper behavior in this life. Knowing this, we should try to drop our complaints and accept things as they are, because suffering comes from our attachment. When we let go, our mind will gradually relax. Because we hang on so tightly to desires, we become increasingly tense, uptight and disagreeable, thus creating more and more suffering.

When I was shown around your dorms, there was a guy who told me he would like to drop his grudge and take things the way they are. Hearing this, I was really happy for him. There was a khenpo Kunga Wangchuk from the Tibetan Sakya tradition who was imprisoned for more than 20 years. After he was released, he went to India. A great master there asked him: “What was your greatest fear in prison? What were you afraid to lose at that time?” He answered: “My greatest fear was to hate those who treated me poorly. What worried me most was that I would lose my compassion.” Please consider this. It’s really quite profound.

Regardless of whether you are a person of faith or not, try to observe your mind – the thoughts, moods and emotions that appear there – because mind is the source of happiness and suffering. With even a little realization of your own mind, your lives will be changed greatly.

Five Tips to Deal With Hard Times

Five Tips to Deal With Hard Times

- Observe your mind and do meditation

I sincerely hope you gain something from my talk. With this intention, I have several pieces of advice for you.

Number one: regardless of whether you are a person of faith or not, try to observe your mind—the thoughts, moods and emotions that appear there—because mind is the source of happiness and suffering. With even a little realization of your own mind, your lives will be changed greatly.

Number two: try to do meditation. It’s better to meditate for five or 10 minutes both in the morning and at night before sleep every day. Try not to think anything and just abide calmly. Also, you can meditate on loving-kindness and compassion, which is a Buddhist approach, or meditate on love according to the teaching in Christianity or whatever faith you follow. About the method of meditation, you can follow the way introduced in your own religion if you have one. It’s good to hear that there are religious activities on Sundays here.

It’s a really good to do retreat in prison. I was told that your working time here is about six or seven hours every day. In this case, you can use the rest of your time to do meditation retreat. Plus, the fact the sun sets very early here at the moment is also a great help for your retreat. In terms of the forms of retreat, in Tibetan Buddhism, there is the tradition of “3 years, 3 months, 3 days” retreat. Participating in such a retreat is very helpful for taming our mind. There is a gentleman with me who has participated in a three-year retreat in France. If time permits, we will take a few minutes to let him share his experience with you. Lots of people enjoy doing meditation retreat in solitary places. If you can, apart from your work and study here, try constantly to observe your mind through meditation. This will help you deal with missing your families, and to avoid distractions from the outside world. Since there are so many distractions out there, maybe it’s better to stay here!

Having been ordained for more than three decades, I’ve been living a very simple and peaceful life. When I was in the US a few days ago, I was invited to watch a ball game together with some Buddhist friends. When we arrived at the court, many people were celebrating under colorful lights with cups of beer in their hands. I was averse to it, and found myself concerned something might be wrong with those people. Perhaps you think that would be a fun thing to do. To me, having one cup of coffee a day, reading books and drinking tea, which is basically my life at the monastery, is very enjoyable and very meaningful for me.

- Read more, be happy and pray

Number three: reading. By reading and studying while you serve your sentences here, when you are released, you will have gained more knowledge and wisdom than you had previously. There are many cases of historical figures, especially writers, who gained superior wisdom through reading during the time when they were imprisoned.

Number four: always be happy no matter what environment you are in. As human beings, I believe we all have an innate desire to be happy. In this respect, we are exactly the same. Without a happy heart, even if you are free physically, your life will be much less meaningful because it’s extremely difficult for an unhappy person to bring any positive influence to one’s family or to society. If you are always happy, and are able to get along well with both the officers and the other prisoners here, your world will be more pleasant. As it is said in Buddhism, “If our mind is well-tamed, even hell becomes heaven; If we fail to tame our mind, even heaven can turn into hell.

There was a Tibetan called Phuntsok Wangyal who spent 18 years in prison from the 1960s until his death a couple of years ago. Initially, before his imprisonment things looked very promising for him. He used to work as the translator for Tibetan Buddhist practitioners and leaders of the CPC central committee, but later fell out of favor due to factors related to social class. Back then, the living conditions in prison were very poor. According to a book he wrote in prison, for the whole 18 years he had never been outside his gray walled cell and had totally lost track of the seasons, and could barely tell day from night. He had nothing but a bun and a handful of rice for food every day. But he never stopped learning and remained a great thinker.

His book was written in such a situation. The ink he used for writing was made from his blue prison uniform. He would moisten his clothes with his saliva, squeeze the liquid out as ink, and write on some thick toilet paper. Sometimes, when he was full of inspiration as he was writing, he would jump to his feet suddenly. The jailers, thinking he might be crazy, would lash him with a whip. Then in the last nine years of his sentence, he played dumb and didn’t say a word any more. When he was finally released, at first he could barely speak to his family because he hadn’t spoken in those nine long years.

One more thing, when you are in a bad mood or are suffering, try to pray to Avalokitesvara by saying “Namo Lokeśvaraye” or chanting “oṃ mani padme hūṃ” which is very important. Avalokitesvara manifests various forms to come to and help sentient beings who are suffering. This is well explained in the Lotus Sutra’s Universal Gate Chapter on Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara.I gave a live-streaming teaching on this chapter last year, and the audience was pretty big. It’s a very short chapter and the Swedish version is available. If you are interested, you can learn it. Regardless of whether one is religious or not, it’s important to believe that there are many profound things in our lives that we can’t see or hear.

It’s been really nice meeting you today. As I said, in Buddhism we regularly do meditation retreats. I’d like to invite my friend to take a few minutes now to share what his three-year retreat in France was like. I hope his words will be an inspiration to you. If you can adjust your state of mind, many things in life will become meaningful. Things that previously seemed to be troublesome may turn out to be very helpful. And things that once gave you reputation, success and happiness might become much less important.

Three-year Retreat Experience

Actually, I didn’t want to speak because Khenpo is such a great master and I’m just an ordinary person. But since Khenpo asked me to, I can’t but speak.

I came in contact with Buddhism in the 1970s. I was kind of a hippie, but I guess there were some other factors in play; I loved reading and was interested in spirituality. I read many books on religion. I realized life doesn’t start at birth and doesn’t end with death. Something happened in my life that convinced me that consciousness exists before birth and doesn’t die with the body. This is how I entered into Buddhism.

I heard that there was a three-year-three-month retreat in France and I had a strong wish to participate. Many things happened at that time. My dad passed away and the Sixteenth Karmapa, a very important teacher for me also passed into nirvana. But later I managed to go to France and participate in the retreat. Being in retreat means you voluntarily break off from the outside world and isolate yourself, not as a punishment, but as a way to avoid distraction.

When I was there in France, there was a very venerated teacher visiting nearby about one kilometer away. I had met him in India before and really wanted to go and see him, but I couldn’t, because of the vow I’d made of doing the retreat. One day my retreat teacher said: “You may go and buy a caravan.” I needed it for the summer as I couldn’t stay in the house where I lived, they needed it for guests. This gave me the chance to visit the teacher from India. One week later, I was in a fully organized retreat together with a dozen or so people. I wasn’t sure that I would be accepted into the retreat, but it happened, and I entered it. It was exactly what I wished for. So I stayed there for three years, voluntarily. I received pith instructions and practiced step by step from the preliminary practices to the most advanced practices. I came out after three years. One might think it would be hard to be around people again after the retreat since I barely spoke to anyone except for sitting and reciting mantras, and doing visualization and meditation.

During the retreat, I meditated a lot on watching my thoughts in a relaxed state. When a thought arises, allow it to arise but do not grasp onto it, and watch it disappear naturally. Actually, all our problems arise from our thoughts and emotions. For example, when the thought of “I don’t like this” arises, it will invoke another thought: “I really don’t like this.”, and then: “I truly hate this!” Afflicted by these thoughts, our behavior and language may upset others, which may trigger problems in one’s mind like generating jealousy, craving, anger or pride. It may also trigger problems between people, even between nations. It’s like taking poison; our lives are poisoned by our afflictions. The real purpose of meditation is to cut off our afflictive emotions because they are the roots of all our suffering. Our emotions affect our body as well. When we are angry, jealous or depressed, our body may hurt as well. It feels like physical pain. Or if we get agitated, we may feel uneasy, and feel a lump in our throat. It is all because of our thoughts and emotions.

The purpose of a retreat is, firstly, to calm your mind. But this is not enough, because if we simply want to calm down, we can just take some pills. What is important is to see through the nature of thoughts and understand our mind more deeply. We discover what is deep inside of us, deeper than thoughts or emotions, and then take a step further to truly realize the nature of mind or Buddha nature (the nature or potential for enlightenment). Buddha nature is present within every sentient being. Buddhism doesn’t mean only Buddhists have Buddha nature and others don’t. Everyone has Buddha nature and is able to realize it. This was the reason I did the retreat.

After the retreat, I went to Nepal, and lived in a Buddhist temple for five years where I was basically in retreat, too. There was no flush toilet, no shower. The toilet was a pit in the ground. When I came back from Norway where I stayed to avoid the rainy season in Nepal, a big tomato plant had grown in that pit I used as a toilet. That was the happiest time of my life, because I could immerse myself in what I wanted to focus on. There was a teacher there who was my main instructor, and from whom I received pith instructions for practice, trying to realize the nature of all phenomena. He passed away 20 years ago.

We so easily become a slave to our afflictive emotions, such as hatred, craving, jealousy, pride, anger, and anxiety. Due to our strong afflictive emotions, we have done many things wrong and have generated lots of negative karma, so we need to free ourselves from these negative emotions. Doing bad things is not good, but it can be changed and we can always make it right, because our thoughts are not real, not concrete, they are not made of steel or carved in stones, but rather they are insubstantial.

There are many examples of this in Buddhism. For example, the Buddha had a disciple named Angulimala who had previously had a crazy teacher who’d told him that: “If you kill 1000 people, cut off their fingers, string them in a chain and hang that around your neck, you will become enlightened.” When he was about to kill his thousandth person, he met the Buddha who told him to stop doing that and taught him how to practice. He practiced accordingly and became enlightened. So nothing is impossible and nothing is set in stone.

The Meaning of Asceticism by Khenpo Sodargye

The Meaning of Asceticism by Khenpo Sodargye

Question #1:

During your early years as a monk you were very poor. Was that to cultivate self-discipline?

Khenpo Sodargye:

Yes, that’s right. Before being ordained, I studied at a college for teacher training. If I had become a teacher, I would have ended up very busy with schoolwork, and over time mainstream society would have influenced me. After much reflection, I decided to pursue learning and wisdom, which is more suitable to me and something I’m very interested in, so I chose the ascetic life. Ever since then, the experience of my early days as a monk has left a lasting impression on me; I learned so much during that time. We often forget, suffering and solitude give us an opportunity to engage in deep reflection, enabling us to contemplate on many essential issues. Through deep contemplation, we can realize the extraordinary innate wisdom and compassion in each and every one of us.

Is It an Obligation for Buddhist Teachers to Give Lectures?

Question #2:

In Buddhism, as a spiritual teacher, is it your obligation to travel around and give talks? Is it something you are willing to do, or does Buddhism require you to do it?

Khenpo Sodargye:

It’s certainly not obligatory. I like to do it at the right time. Take this trip for example: Before I come here, I visited the United States, including Chicago, Washington, and New York. Now I am here in Sweden and later I will go to Norway, Switzerland Spain, and Israel. It’s quite an itinerary this time. This trip is happening because I received invitations from universities, prisons and some other social communities and groups. I am willing to accept them and give talks for free. It’s not only one way, I also learn a lot from people of different backgrounds. More importantly, I hope that through sharing Buddhist teachings with them, people will benefit.

Do Buddhists Practice Kungfu?

Question #3:

Do Buddhists do physical exercise, I mean, Kungfu or something like that?

Khenpo Sodargye:

Actually, Shaolin Kungfu is mainly practiced within the Shaolin tradition – monastics of other Han Chinese and Tibetan monasteries do not really know it. Before ordination, I often did workouts with a punching bag. I would fill a bag with sand, hang it up, and then start boxing with it. After being ordained, I never did it again. The Shaolin Temple in China has successfully trained a lot of Kungfu monks, especially during the last century. This may be why many people today mistake all Han Chinese monks as Shaolin monks. The monk accompanying me on this trip was mistaken to be a Shaolin monk several times when we were at airports.

There are teachings in Buddhism about Kungfu, but very few, because Buddhism mainly focuses on developing one’s inner strength rather than practicing Kungfu; that is, cultivating our unsuspected inner abilities, such as gaining inner peace and realizing the meaning of life.

Observing Root Precepts Is the Basis for Peace and Happiness

Question #4:

What kind of discipline does one have to observe in order to find inner peace or happiness?

Khenpo Sodargye:

There are mainly four root precepts in Buddhism, which can also be found in Christianity. They were laid down by the Buddha to guide people’s behavior 2,500 some years ago. The four root precepts are: not to kill human beings; not to steal; not to tell lies; and not to engage in sexual misconduct. What constitutes stealing is clearly described in the Vinaya. No sexual misconduct means not to have sexual relations with anyone besides one’s spouse. These four precepts are observed by all Buddhists, monastics and lay alike. Observing these precepts is essential for us because if we don’t violate them we will find happiness in this world.

Does Khenpo Like Swedes Dishes?

Question #5:

How do you like Swedish cooking?

Khenpo Sodargye:

Yesterday I dined at a vegetarian restaurant and saw many young Swedes enjoying vegetarian meals, and I notice that lots of Swedes prefer vegetarian food for the purpose of staying healthy and saving animals’ lives. So this morning I published a post on Weibo about this. Personally, I like Swedish cuisine more than American food. But food from my hometown is my favorite!

Which Is the Worst Prison Khenpo Has Visited?

Question #6:

Which is the worst prison you have been to?

Khenpo Sodargye:

There is one prison where, as I’ve heard, many holes were dug to bury prisoners alive. The situation there is much better than it used to be, and prisoners aren’t treated like that anymore. But when I visited there, there were about two or three hundred inmates who were all shackled on their hands and feet, and still sometimes being physically attacked. Although many prisons are equipped with monitors to keep prisoners from being tortured, still some places are horrendous.

Basic Meditation Technique for Inner Peace

Question #7:

In Buddhism, how does one empty one’s mind – by reciting mantras or other methods?

Khenpo Sodargye:

Normally, meditating in the seven-point posture of Vairochana is a good way to calm the mind. There are seven points to follow:

1) Sit in the lotus posture of Vairochana.

2) Palms facing up, right over left, below the abdomen.

3) Relax your shoulders, allowing them to drop naturally.

4) Straighten your spine.

5) Slightly lower your chin.

6) The tip of the tongue touches the palate.

7) Gaze out into the space in front of you.

Sitting in this posture, breathing slowly, our thoughts will naturally disappear and our mind will calm down. Eyes can be closed or open, both are ok. Set an appropriate time for meditation that suits you: five minutes, ten minutes, or thirty minutes. It’s ok to rest mind in peace without thinking anything; or to be mindful, observing what your mind is doing at the moment. Generally, relax your mind and body. If you meditate in this way every day for a period of time, your mind will become more peaceful.